Last Sunday I went on a day trip to Ravenna with two French women from my language school. I had been there many years ago during my first trip to Italy, and was glad to have an opportunity to pay a return visit.

Ravenna is an unusual city. It was actually the capital of the Western Roman Empire for a while. It was moved there from Milan by Honarius in 401 when the Empire was under threat from the Visigoths. Ravenna, surrounded by water, a bit like Venice, was thought to be easier to defend. The Visigoths didn’t seem to take much notice of this move; they marched down to Rome and sacked it in 410, as we all learned in school, thus initiating the beginning of the end for the Western Empire. While there, they took captive Galla Placidia, daughter of the previous emperor Theodosius I and sister of Honarius. Ravenna remained the capital of the Empire until it ceased to exist in 476, after which it was the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy, and then briefly part of the Eastern (Byzantine) Empire. The various works of art in Ravenna provide a unique record of this transitional period from the late classical to the byzantine, and the beginnings of medieval.

Our first stop was the Arian Baptistery. Some explanation might be in order first. At the time it was built, around the end of the 5th century, Italy was ruled by the Ostrogoth Theodoric. Theodoric became King of Italy by killing the previous King of Italy, the Ostrogoth Odoacer, at the suggestion of the eastern Emperor Zeno. Odoacer had nominally been a vassal of the Emperor, but in reality was quite independent. In fact, he led a revolt which deposed the Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, in 476, which as noted is usually taken as the ‘official’ end of the Western Empire, though there was in fact another Western Emperor after Romulus Augustulus (I’ve always loved that name; seems like something out of Life of Brian). When Odoacer proved too much for the Eastern Emperor to control, he had the Goth Theodoric take care of him. The imperial armies had for some time been manned by ‘barbarians’.

The Ostragoths had been converted to Christianity some time before, but as the theology of Christianity was still somewhat fluid in those days, they had been converted to a form of Christianity that held Christ to be somewhat less of a god than God. This stressed Christ’s humanity, and apparently had some impact on the imagery used by the Arians, though it’s hard to say since virtually none of it has survived, aside from Theodoric’s Arian Baptistery.

The baptistery is a pretty modest looking affair from the outside, looked over somewhat casually by a guy who has no tickets to sell or check. Inside, though…

there is a magnificent ceiling mosaic. It shows the twelve apostles (as then conceived) holding crowns and marching in procession towards a throne.

In the middle is a representation of Christ’s baptism. It is commonplace to point out that the humanity (as opposed to divinity) of Christ is accentuated in this representation, most notably by his clearly visible naughty bits under the water. This is thought to be theologically significant, in light of the Arian views of the semi-divinity of Christ. No one really knows exactly what the Arians of Theodoric’s court thought, though, and there are precious few, if any, other Arian representations at all, let alone of the baptism of Christ, from which to draw stylistic generalizations. In fact, as we’ll see, the imagery in the baptistery was based on that of the older Neonian baptistery in town.

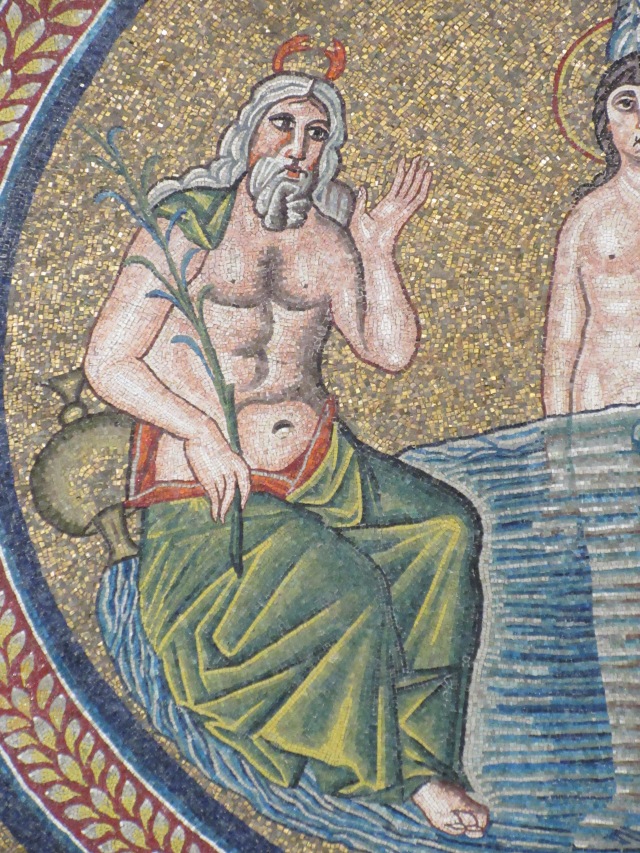

John the Baptist is to the right of Christ, while a very standard classical representation of a river god, in this case that of the Jordan, is on the left, complete with overturned amphora. You might remember this type of representation from the San Carlino. Are those crab claws on his head?

The apostles, rather than paying attention to the ‘human’ Christ, proceed towards a representation of Christ Risen, i.e., the cross on the throne. This, presumably, is a representation of the more divine nature of Christ, according to Arian theology, and probably marks the biggest divergence from standard Catholic iconography. Sts Paul and Peter flank the throne, Peter with his keys, and Paul, uncharacteristically, with scrolls instead of a sword. They do look like all the standard representations of Paul and Peter, though, the former with dark hair, a long beard, and male pattern balding, the latter with curly white hair and short beard. I’ve always wondered where these representations came from.

On our way to the next stop, we took a little detour to pay our respects to Dante.

He was kicked out of Florence after getting on the wrong side of the Guelph/Ghibelline conflicts (more accurately, getting on the wrong side of the black and white Guelph conflicts after the Ghibellines had been defeated in Florence). He ended up in Ravenna, where he died, and from which Florence has ever after been trying to get his bones back.

The next stop was the Neonian Baptistery.

As noted, this predates the Arian Baptistery, and most likely served as the model for the latter’s mosaics. The mosaics date from the end of the fifth century, at the time of Bishop Neon. The design is almost identical to the mosaic we just saw.

In the center, Christ, bearded this time, is being baptized, with John the Baptist on one side and a personification of the river Jordan on the other. In an outer ring is a procession of the twelve apostles. This time, though, they’re not marching to a representation of Christ’s divinity, since presumably Christ is already divine in the center picture, and doesn’t need a stand in. As before, Peter and Paul are in the lead, with Peter looking as he always does, with short white hair and trimmed white beard.

Unlike the Arian Baptistery, there’s an outer ring with some really wonderful decoration.

Here again is Christ’s throne, though not the center of adoration as before.

It’s remarkable to me that this represents art from the late Roman Empire, in such a wonderfully preserved state.

Next stop was the Basilica of San Vitale.

This was begun under the Ostrogoths, but before it was finished, the Eastern (Byzantine) Emperor Justinian, or rather his general Belasarius, had retaken Ravenna, and thus the Basilica ended up being decorated with what are the finest Byzantine mosaics in the west.

The church is octagonal, like the baptisteries, but had a very different feel due to the unusual ambulatory around it.

The original entrance was off at an odd angle, with an external door leading to a wall and two side entrances, immediately disorienting the visitor as they entered what is already a fairly disorienting space. That experience unfortunately no longer exists, but it’s still quite a thrill walking in and seeing the apse mosaics for the first time.

In the center is a clean-shaven, classical looking Christ, decked out in imperial purple, sitting on the globe, handing a martyr’s crown to Saint Vitale. On his other side, Bishop Ecclesius holds a model of the church. These figures are very helpfully labeled.

On the sides are mosaics representing various Old Testament sacrifices.

as well as other Old Testament figures.

Among the most interesting – and most celebrated – mosaics are those of the Emperor Justinian and his wife, Theodora.

The rule of thumb for determining who was where in the hierarchy, aside from the relative sizes of the figures, is to look at who is stepping on whose toes. This is most obvious in the portrait of Justinian.

Within the San Vitale complex is the tomb of Galla Placidia, daughter of the emperor Theodosius and sister of Honarius. She led quite a life, which I will leave to you to discover at your leisure.

While there is some debate over whether this structure was ever really intended to be a tomb – Galla Placidia’s mortal remains supposedly reside in Rome – the pine cone on the roof, a Roman sign of death, would seem to indicate it was meant to be a home for the departed.

This is a 5th century building, and truly a late Roman building, with remarkable classical mosaics from that period.

Most notable is the representation of Christ as the Good Shepherd, with Christ looking more like Apollo than the gaunt, bearded fellow we’re used to seeing. Also of interest is a mosaic of St. Lawrence, who was martyred by being grilled on a gridiron.

His last words, according to the official biography, were “I’m done on this side, you can turn me over now.” I can’t really imagine what connection St. Lawrence, who is the patron saint of Spain, might have had to Galla Placidia.

Peter and Paul also make an appearance, looking much as they always do, albeit with white robes, rather than the robes of gold/blue and red/green, respectively, that they later acquired. Flash photography was not allowed in this building, and there was little light, so I apologize for the quality – or lack thereof – of the photos.

The last stop on our tour was St. Apollinare Nuovo.

This was originally built by the Arian Theodoric as his palace chapel, but after Justinian retook Ravenna it was ‘rehabilitated’ to be an orthodox church. There is another St. Apollinare in nearby Classe, and that is actually the newer church. St Apollinare Nuovo, while older, was dedicated to St. Apollinare after the church in Classe was, hence the chronologically confusing name.

The church is in basilica form, with a procession of male and female martyrs above the columns on either side, and above this some remarkable 6th century mosaics from the time of Theodoric representing Christ’s miracles/parables on one side, and the passion on the other. Notably, Christ is depicted as a young man in the miracle mosaics and as the more familiar bearded sage in the passion mosaics, showing a distinction which was probably more suitable to Arian theology than orthodox theology.

Here is the miraculous draught of fishes, with St Peter hauling up the net.

And here is the separation of the sheep from the goats (i.e., the good people/nations from the bad). The angel in blue on the right is thought by some to be the first Christian representation of the devil. In both of these panels Christ looks like a young emperor, not that dissimilar from the mosaic in the mausoleum. Note how less naturalistic Christ is in this later mosaic, though. Clearly some of that classical finesse had been lost by this point.

On the other side of the nave are scenes from the passion. Here is an interesting representation of the Last Supper.

What is remarkable to me about this is that everyone is reclining around the table during the meal, as would have been the case in Rome. Also, instead of a lamb, the meal involves fish. Note that Peter is lying next to Christ; he’s always easy to recognize.

This is the kiss of Judas, one of the few panels with a figure that isn’t static.

At the back of the processions of martyrs are a scene of the Royal Palace of Theodoric on one side and the port of Classe on the other. Here is the port, with a few boats in the harbor.

The gold bricks underneath the town of Classe were obviously newer additions, though I don’t know what they were meant to cover.

In the case of the Palace of Theodoric, the motivation behind later modifications is a little more obvious. In the panel below you can see Palatium written on the main building, with Ravenna in the background.

But the palace has mysterious curtains between the columns. What can this mean? Well, after Ravenna was taken over by Justinian, any representations of Theodoric and his court would not have been appreciated. So while portraits of Theodoric and his people would undoubtedly have occupied the spaces between the columns, they were worked over by Justinian’s artists. However, in some cases their arms extended beyond the spaces, leading to some oddly disembodied extremities.

In fact, if you look closely you can see ghostly shadows of the heads of the figures above some of the curtains.

Similarly, when the church was taken over by the Orthodox Justinian from the Arian Theodoric, it was rededicated to St. Martin of Tours, who was a staunch opponent of Arianism, and a portrait of St. Martin was added at the head of the line of martyrs.

Martin, however, was not a martyr, so he seems a bit out of place here. Note that he isn’t holding his martyr’s palm, as are all the fellows behind him in line.

After our long march through Ravenna we were hot, tired and thirsty, and so set off for the port to have a refreshing look at the sea. Alas, the port was not terribly picturesque.

But it did afford us our final, fitting mosaic of the day.

As a side note, you may have noticed the dearth of posts lately. As you might have guessed, I’ve had little time in the past few weeks. I’m in Torino now, and very near the end of my stay here. Thus, this will likely be my last post, though of course there’s much more to tell. That will have to wait until I see you all again.

A presto…

Thanks for this tour of fascinating Ravenna with its amazingly well preserved treasures of late Antiquity!

LikeLike